Blog Article

Auburn Football 2025 Season Preview: Hugh Freeze’s Make-or-Break Season Arrives

Auburn’s Hugh Freeze is running out of time.

After two straight losing seasons at Auburn, the Tigers head coach faces the most critical year of his tenure on the Plains. Everything that could be upgraded has been upgraded. The quarterback room features a former five-star transfer. The roster is loaded with blue-chip talent from back-to-back top-10 recruiting classes. The transfer portal has been pillaged for immediate impact players.

But none of that matters if Auburn can’t win football games.

The 2025 season isn’t about potential anymore—it’s about production. And for Freeze, it’s about survival in the unforgiving world of SEC football.

Jackson Arnold Solves Auburn’s Biggest Problem

Auburn’s quarterback situation has been solved.

Oklahoma transfer Jackson Arnold brings the exact skill set that Hugh Freeze’s offense demands: dual-threat ability, RPO mastery, and a cannon for an arm. Arnold isn’t just an upgrade—he’s a complete transformation of what Auburn can do offensively.

His 2024 numbers at Oklahoma tell only part of the story:

- 1,421 passing yards, 12 touchdowns, 3 interceptions

- 444 rushing yards, 3 touchdowns

- 131 rushing yards in upset win over No. 7 Alabama

“The fit he is for our offense and Auburn, I couldn’t be more excited,” Freeze said. “He’s a dual-threat guy who understands the RPO system extremely well and throws the deep ball extremely well.”

Arnold struggled at Oklahoma due to receiver injuries and the presence of three different offensive coordinators in one season. At Auburn, he’ll have stability, weapons, and a system designed to capitalize on his strengths.

This is the quarterback Auburn has been searching for since Cam Newton left the Plains.

The Transfer Portal Became Auburn’s Salvation

Auburn attacked the transfer portal like their program depended on it.

Because it did.

The Tigers identified every weakness from 2024 and found proven solutions in the portal. Offensive line struggles? Virginia Tech’s Xavier Chaplin and USC’s Mason Murphy arrive with starting experience. Receiver depth issues? Georgia Tech’s Eric Singleton Jr. brings elite production and versatility.

The defensive side received similar treatment:

- MAC Defensive Back of the Year Raion Strader

- Experienced linebacker Caleb Wheatland

- Multiple defensive backs with Power Five starting experience

Auburn brought in 19 transfers while losing 23 players to the portal. However, the key difference lies in this: most departures weren’t regular contributors, whereas most additions had starting experience.

This wasn’t roster management—this was strategic reconstruction.

Elite Recruiting Finally Pays Dividends

Auburn’s recruiting renaissance under Hugh Freeze has been impossible to ignore.

Back-to-back top-10 recruiting classes have fundamentally changed the talent level on the Plains. The 2025 class ranks No. 6 nationally and includes:

- Five-star quarterback Deuce Knight

- Five-star edge rusher Jared Smith

- Eight of Alabama’s top-10 prospects

- Multiple ESPN 300 contributors across all positions

“I inherited a program that didn’t have a top-25 recruiting class for 4 years,” Freeze acknowledged. “You’re not going to win in this league [with that]. We’ve now had 2 full recruiting classes, both top-10.”

The talent gap that existed between Auburn and SEC powers has been closed through recruiting. Now comes the harder part: developing and deploying that talent effectively.

Defense Gets Rare Continuity

Here’s something Auburn hasn’t had in years: defensive coordinator stability.

D.J. Durkin returns for his second season leading the defense, providing continuity in a program that has cycled through coordinators at breakneck speed. The 2024 defense showed flashes of dominance when healthy, averaging 7 tackles for loss and 2.3 sacks per game.

The secondary remains Auburn’s defensive strength:

- Experienced starters Kayin Lee and Kaleb Harris return

- Transfer addition Raion Strader brings All-MAC credentials

- Depth improved through recruiting and portal additions

Auburn must replace five of its top seven tacklers, but the combination of returning talent and strategic additions provides optimism for significant improvement.

The defense has the pieces—now Durkin gets an entire season to implement his system without major personnel overhauls.

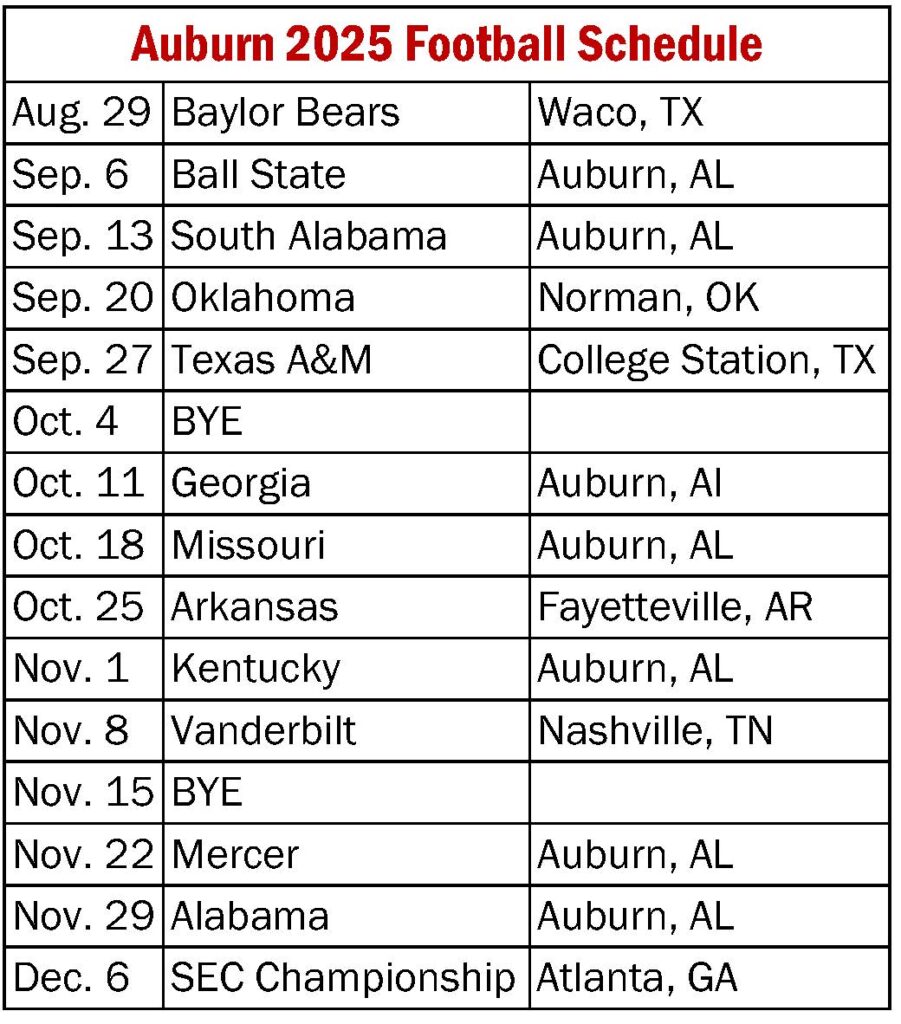

The Schedule Helps Auburn

Auburn’s 2025 schedule is the most favorable they’ve seen in years.

Ranked 15th nationally in strength of schedule and 12th in the SEC, the Tigers avoid some of the conference’s most dangerous programs while their most significant challenges at Jordan-Hare Stadium.

Key scheduling advantages:

- Alabama and Georgia both visit Auburn (historically better for the Tigers in odd years)

- No matchup with Texas, the SEC’s most dominant program

- Manageable non-conference slate to build momentum

- Oklahoma visit provides revenge game opportunity against Arnold’s former team

“I feel a lot better than I have about our talent, our size, athleticism, and depth,” Freeze shared. “I still believe we need one more [signing] class to get to where we need to be, but I don’t sense any panic.”

The schedule provides Auburn with realistic paths to 7-8 wins if the talent translates into performance.

Hugh Freeze’s Job Depends on One Thing

Bowl eligibility isn’t a goal for Auburn in 2025—it’s a requirement.

“I’m not a fool, I think we’ve got to go to a bowl game,” Freeze said publicly. This represents the minimum acceptable outcome after two years of elite recruiting and massive roster investment.

The pressure couldn’t be more obvious:

- Two straight losing seasons

- Back-to-back years missing bowl games

- Massive financial investment in roster construction

- Fan patience is completely exhausted

Freeze’s track record suggests confidence in reaching this baseline. In 12 seasons as an FBS head coach, he’s failed to win six games only twice: his final year at Ole Miss and his second year at Auburn.

But Auburn hasn’t just invested in talent—they’ve invested in Freeze’s vision. If that vision doesn’t produce wins in 2025, both will be replaced.

The Areas That Will Define Success

Auburn’s 2025 season will be determined by improvement in specific areas.

Red zone efficiency was a key factor in the Tigers’ struggles in 2024, ranking 122nd nationally in touchdown percentage. Arnold’s dual-threat ability and upgraded receivers should immediately address this critical weakness.

Special teams ranked 84th nationally in SP+ efficiency, consistently hurting field position and momentum. New specialists and renewed emphasis represent clear priorities.

Turnover margin must improve after Auburn averaged 1.8 giveaways while forcing only 1.1 takeaways per game. Arnold’s decision-making will be crucial in flipping this equation.

These aren’t complex problems—they’re execution issues that talent alone should be able to solve.

What Success Looks Like

Vegas set Auburn’s win total at 7.5 games, reflecting cautious optimism about the program’s trajectory.

ESPN’s SP+ model projects Auburn to rank No. 25 overall, with an average of 6.9 wins. The defense is projected to rank 19th nationally, while the offense is projected to rank 48th. These numbers suggest a team capable of bowling with upside for more.

Realistic 2025 benchmarks:

- Bowl eligibility (minimum acceptable outcome)

- Competitive showings against Alabama and Georgia at home

- Road victory against Oklahoma or Texas A&M

- Establishing clear program momentum for 2026

The talent is there. The schedule cooperates. The expectations are clear.

Now, Auburn has to win football games.

The Bottom Line: No More Excuses

Auburn enters 2025 with everything necessary for success.

The quarterback position has been upgraded with a proven dual-threat transfer. The skill positions feature elite recruiting and portal additions. The defense returns key contributors while adding impact players for depth.

The schedule provides legitimate opportunities for 7-8 wins. The roster construction represents a substantial financial investment in immediate success.

Hugh Freeze has spent two years building this foundation. The 2025 season will determine whether he can coach at the level he recruits, or whether Auburn needs to find someone who can.

The excuses have been exhausted. The expectations are crystal clear. The pieces are in place.

Time to find out if Hugh Freeze can turn all this potential into actual victories.

The Next Billion Dollar Game

College football isn’t just a sport anymore—it’s a high-stakes market where information asymmetry separates winners from losers. While the average fan sees only what happens between the sidelines, real insiders trade on the hidden dynamics reshaping programs from the inside out.

Our team has embedded with the power brokers who run this game. From the coaching carousel to NIL deals to transfer portal strategies, we’ve mapped the entire ecosystem with the kind of obsessive detail that would make a hedge fund analyst blush.

Why subscribe? Because in markets this inefficient, information creates alpha. Our subscribers knew which coaches were dead men walking months before the mainstream media caught on. They understood which programs were quietly transforming their recruiting apparatuses while competitors slept.

The smart money is already positioning for 2025. Are you?

Click below—it’s free—and join the small group of people who understand the real value of college football’s new economy.