Blog Article

Gridiron Gambles: The 10 College Football Coaches Walking a Tightrope

In the high-stakes college football arena, where careers are made and broken on the whims of boosters and the bounce of an oblong ball, ten men are perched precariously on the edge of oblivion. “Gridiron Gambles: The 10 College Football Coaches Walking a Tightrope” isn’t just a headline—it’s a window into the soul-crushing, sweat-soaked world where multimillion-dollar contracts collide with the harsh realities of wins and losses. From the Appalachian highlands to the sun-baked plains of Texas, these coaches navigate a landscape where success is measured in increments of eternal optimism and crushing disappointment. Their stories, a cocktail of ambition, desperation, and financial engineering, reveal the true nature of an industry where the difference between genius and failure is often nothing more than a well-timed trick play or a kicker’s wayward foot.

In the peculiar economy of college football, where success is measured in increments of eternal optimism and crushing disappointment, Shawn Clark finds himself caught in the undertow of expectations at Appalachian State. The numbers tell one story: 39-23 since taking the helm in 2020, a winning percentage that would keep most mid-major coaches comfortably employed. But numbers, as any good statistician will tell you, can lie by omission.

What the raw data fails to capture is the psychological toll of regression. The Mountaineers weren’t just expected to be good in 2023 – they were supposed to be the darlings of the Group of Five, the team that might crash the party of college football’s elite. Instead, they’ve become a case study of the dangers of potential unrealized. At 4-5, with games against James Madison and Georgia Southern looming like storm clouds on the horizon, Clark has managed to do something remarkable: he’s made winning 63% of his games feel like a failure.

The truly fascinating part isn’t that Clark might lose his job – it’s that he’s demonstrated how quickly the currency of past success can be devalued by present disappointment. In the modern college football marketplace, where fans trade in the futures market of expectations rather than the commodity market of actual wins, Clark’s greatest sin wasn’t losing – it was making people believe they could win more.

Contract and Buyout: The Price of Promise

To understand the true economics of college football’s expectations game, look no further than the elaborate financial instrument known as Shawn Clark’s contract. It’s a document that reads like a futures trading agreement, where the underlying commodity is hope itself. The university has systematically increased its investment in Clark yearly – from $775,000 in 2021 to $925,020 in 2023 – a nearly 20% appreciation in perceived value over just two years. This comes complete with a monthly “retention bonus” of $22,085, which seems precision-engineered by some unseen actuary to satisfy Clark just enough to stay.

But it’s in the buyout structure where the real financial engineering reveals itself. The university created what Wall Street would recognize as a descending ladder of put options – starting at $5 million and stepping down to a mere $250,000 by 2025. It’s the kind of carefully crafted exit strategy that investment bankers admire, protecting both parties while gradually reducing exposure. The genius is in how it mirrors the depreciation of both risk and potential – like a financial instrument slowly losing its time value as it approaches expiration.

The contract extension through 2026 tells its own story – one of institutional optimism colliding with the harsh reality of on-field results. However, it’s worth noting – and this is where the fine print becomes crucial – that these buyout figures come from Clark’s initial contract signed in December 2019. Like any sophisticated financial instrument, the terms may have been restructured during his 2021 extension. In the opaque world of college football contracts, such details often remain sealed in filing cabinets, known only to agents, attorneys, and athletic directors until they become relevant.

In the risk-obsessed college football world, where athletic directors typically rush to extend their coaches’ contracts at the first sign of competence, Charles Huff’s situation at Marshall stands as a fascinating market inefficiency. Here’s a coach entering the twilight of his original six-year contract – a virtual unicorn in modern college athletics – with no extension in sight and a buyout figure that reads more like a mid-level administrator’s salary than a Power Five coach’s exit package: $125,917.

The number itself tells a story. Not $125,000, not $126,000, but $125,917. It’s the kind of precise figure that suggests it was calculated by someone who believes in the power of actuarial tables and compound interest rather than the typical athletic department mathematics of ego and escalation.

What makes this situation particularly remarkable is its rarity. In an industry where coaches typically receive extension after extension – often before proving their worth – Huff operates in a state of contractual purgatory. His original 2021 deal will expire at the end of next season, creating the sort of uncertainty that athletic directors typically avoid, like a blocked punt. It’s as if Marshall accidentally discovered a new way to incentivize performance: by doing absolutely nothing.

This arrangement is a controlled experiment in coaching motivation. While his peers coach with golden parachutes worth millions, Huff operates with a buyout that wouldn’t cover the cost of a decent offensive coordinator in the SEC. It’s the kind of situation that would make Billy Beane smile. This market inefficiency either proves the conventional wisdom about coaching contracts wrong or demonstrates exactly why such wisdom exists in the first place.

Ultimately, Huff’s contract situation reads less like a strategic decision and more like an oversight – as if Marshall’s athletic department forgot to follow the standard operating procedure of college football’s coaching carousel. The question isn’t whether this approach is brilliant or foolish but whether it was an approach at all.

If you wanted to design a perfect experiment to test the breaking point of college football’s traditional patience with new coaches, you couldn’t do better than the case of Kenni Burns at Kent State. His record reads like a Silicon Valley startup’s burn rate: 1-22 overall, hemorrhaging games at a pace that would make even the most optimistic venture capitalist nervous. But what happened off the field transforms this from a simple story of athletic underperformance into something far more revealing about the economics of mid-major college football.

In a move that defied conventional market logic, Kent State doubled down on its investment in February 2024, extending Burns’ contract through 2028. Just months later, a local bank would be suing their head coach over $23,852.09 in credit card debt, representing roughly 4.5% of his annual salary. It’s the kind of financial disconnect that would make a Wall Street risk manager break out in hives: a man making half a million dollars annually defaulting on a credit card from the same community bank that once sponsored the school’s baseball program.

The financial architecture of Burns’ deal reveals the strange economics of mid-major college football. His base salary – starting at $475,000 and climbing to $515,000 – comes wrapped in a series of micro-incentives that read like a behavioral economist’s experiment in motivation. There’s $5,000 for beating Akron in the battle for the Wagon Wheel trophy (a sum that somehow manages to overvalue and undervalue a rivalry game simultaneously), and up to $15,000 for hitting academic benchmarks – as if to say, “If you can’t win games, at least make sure the players can read about them.”

But it’s in the confluence of the guarantee game clause and the credit card debt where the real story emerges. While up to $200,000 per year from Power 5 “guarantee games” goes directly to the football budget – effectively creating a financial instrument where Kent State profits from their competitive irrelevance – their head coach couldn’t manage to keep current on a $20,000 credit limit. The excuse of “a recent remodel and move” reads less like a justification and more like a perfect metaphor for the program: renovating while the foundation crumbles.

The buyout figure of $1.51 million after 2024 now looks less like an insurance policy against success and more like a cautionary tale about financial due diligence. In the strange economy of college football, Kent State potentially has to pay seven figures to part ways with a coach who couldn’t pay his credit card bill.

This is no longer a coaching contract; it’s a case study of the disconnect between institutional faith and personal finance. Every clause, every bonus, every carefully worded incentive tells the story of a program trying to convince itself that patience is still a virtue in an industry that traded that commodity away years ago. At 1-22, with their head coach dodging debt collectors, they’re not just losing games; they’re conducting an expensive experiment in the limits of institutional faith while their coach conducts his experiment in the limits of credit.

The most telling detail might be the timing: Burns’ team was 60 days past due on its payments to Hometown Bank and past due on delivering a single win in the 2023 season. In college football’s economy, some debts seem more forgivable than others.

In college football economics, Neal Brown’s contract at West Virginia is a case study in the psychology of institutional momentum. Here’s a coach who parlayed a 9-4 season into what might be the most elaborately structured compensation package in the mid-tier Power Five – a document that reveals more about the anxieties of college football administration than it does about winning football games.

The raw numbers tell one story: a $4 million base salary escalating to $4.4 million by 2027, a buyout structure that would make a Wall Street severance specialist blush ($9.525 million if terminated after this season), and a bonus structure so intricately layered it resembles a hedge fund’s fee schedule more than a coaching contract. But it’s in the timing that the real story emerges.

What makes Brown’s situation particularly fascinating isn’t just the money – it’s his apparent reconceptualization of the product he’s being paid to deliver. In October, after another loss to a ranked opponent (bringing his record against Top 25 teams to a sobering 3-16), Brown offered the most revealing quote in modern college football: “Did they have a good time? Did they enjoy it? It was a pretty good atmosphere. I’m assuming they had a pretty good time tailgating.”

It was the kind of statement that would make a McKinsey consultant proud – a brilliant pivot from measuring success by wins and losses to measuring it by customer satisfaction with the peripheral experience. Brown reframed a football program as an entertainment venue, suggesting that the actual game might be incidental to the tailgating experience. It’s as if the CEO of a struggling restaurant chain decided to focus on the quality of the parking lot rather than the food.

Brown’s contract’s genius—or perhaps madness—lies in its bonus structure. It reads like a Choose Your Own Adventure book written by an accountant: $100,000 for eight wins, $125,000 for nine, and up to $200,000 for running the table. Notably, nowhere in the contract is there a bonus for enhancing the tailgating experience.

But it’s in the perks where the true nature of college football’s economy reveals itself. Two courtesy vehicles, a country club membership (funded through “private dollars” – a distinction that speaks volumes about the creative accounting of college athletics), and a $5,000 allowance for university apparel. Even the ticket allocations are meticulously detailed: 25 premium tickets or a suite for football, five for basketball, and 20 for bowl games – enough to host quite a tailgate party of his own.

The buyout clause – 75% of the remaining salary if terminated without cause – stands as a monument to institutional fear: fear of being wrong or right or having to admit either. At current projections, that’s $9.525 million to say goodbye to a coach who might finish 5-7, make a bowl game, or do just enough to make everyone wonder if next year will be different. Or perhaps, given his new metrics for success, just enough people might have a good time tailgating to make it all worthwhile.

In the end, Neal Brown’s tenure isn’t just about coaching football – it’s about an institution trying to put a price on hope while their coach redefines what hope means. Each clause, each bonus, and each carefully worded provision reveals a program desperate to believe it has found its answer while simultaneously hedging against the possibility that it hasn’t. At 5-5, Brown isn’t just managing a football team – he’s curating an entertainment experience worth millions, where the game might be an excuse for the party in the parking lot.

In the complex marketplace of college football coaching talents, Kevin Wilson’s career trajectory reads like a case study in the industry’s peculiar definition of failure and success. Here’s a coach who helped orchestrate some of the most prolific offenses in college football history at Oklahoma, got fired from Indiana for winning too little, landed at Ohio State, where he helped set conference records, and then – in a move that defies conventional career logic – chose to take over at Tulsa, where he’s currently orchestrating what might be called a masterclass in proving why offensive coordinators don’t always make great head coaches.

The numbers tell a story that no Wall Street analyst would want to pitch to investors: 7-13 at Tulsa, adding to a career head coaching record of 33-60. But the path to those numbers makes Wilson’s case so fascinating. This is a man who once presided over an Oklahoma offense that scored 716 points in a season (still third-best in FBS history), helped develop multiple Heisman Trophy finalists at Ohio State, and somehow managed to make Indiana’s offense lead the Big Ten in passing – a feat roughly equivalent to making Vermont a skiing powerhouse.

Wilson’s career is exciting because it perfectly captures the football industry’s inability to value talent properly. Here’s a coordinator who helped create offensive systems that generated billions in revenue for major programs, yet when given his own program at Indiana, was dismissed after going 6-6 – a record that at Indiana should have earned him consideration for canonization rather than termination. The official reason was “mistreatment of players,” but in college football’s economy, winning six games at Indiana while losing the PR battle proves about as sustainable as a crypto startup with good fundamentals but an evil Twitter presence.

The move to Tulsa represents the greatest market inefficiency in college football or its most predictable regression to the mean. Wilson left a position at Ohio State where he was helping generate NFL quarterbacks like a factory assembly line to take over a program where success is measured in bowl eligibility rather than national championships. It’s as if a quantitative trader left Renaissance Technologies to manage a local credit union’s investment portfolio.

The tragedy isn’t that Wilson is failing at Tulsa – it’s that his career perfectly illustrates college football’s inability to distinguish between the skills needed to coordinate an offense and those required to run an entire program. His genius for designing plays that made Oklahoma and Ohio State unstoppable hasn’t translated into the ability to make Tulsa merely competitive. It’s the coaching equivalent of the Peter Principle: promoting someone until they reach their incompetence, except in this case, Wilson chose his promotion.

Ultimately, Kevin Wilson’s story isn’t just about wins and losses – it’s about how college football’s market for coaching talent consistently misvalues specialized skills. His career path from offensive mastermind to struggling head coach serves as a reminder that in college football’s economy, being brilliant at one thing doesn’t guarantee even basic competence at the next level up. At 3-5 this season, Wilson isn’t just coaching football – he’s providing a cautionary tale about the dangers of mistaking tactical brilliance for strategic leadership.

Some numbers tell you everything you need to know about a program’s soul. At Auburn, that number is $68 million – paid not to win games but to make coaches disappear since 2000. The figure transforms a football program into a case study of institutional behavior, like watching someone set fire to their house because they didn’t like the paint color.

Hugh Freeze arrived on the Plains as the latest solution to a problem Auburn can’t quite define. His 2-5 record wouldn’t be remarkable at many places, but it’s just the latest chapter in a story of perpetual dissatisfaction at Auburn. The Tigers have fired a coach two years after winning a national title (Gene Chizik), dismissed another despite his beating Alabama in odd-numbered years with mystifying regularity (Gus Malzahn), and scrapped Bryan Harsin for the crime of not being from around here.

What makes Freeze’s situation fascinating isn’t just his struggles – it’s how carefully Auburn planned for them. His contract reveals an institution that has learned one lesson from its past: how to structure a buyout. While previous coaches like Malzahn ($21.5 million) and Harsin ($15.6 million) had to be paid off like desperate ransom demands, Freeze’s $20.3 million sendoff can be stretched out in monthly installments through 2028, like a mortgage on mediocrity.

The cruel irony is that Freeze, hired to fix Auburn’s offense, has instead provided a masterclass in offensive futility. His team ranks among the SEC’s worst in scoring despite generating 444.5 yards per game – they’re breaking down exactly where the end zone comes into view. It’s as if someone hired Picasso to paint their house, and he insisted on using his feet.

Yet Freeze might survive, at least temporarily, because of a recruiting class ranked fifth nationally – though, as Texas A&M recently demonstrated by signing a top-20 class a month after firing Jimbo Fisher, even that achievement comes with an asterisk in the NIL era.

At 2-5, with five opponents ahead who all have better records, Freeze is approaching territory that not even Auburn’s most creative accountants can rationalize. He’s already matching Bryan Harsin’s pace toward dismissal and doing it with an offense that makes three yards and a cloud of dust look innovative.

The most revealing detail might be this: Auburn structured Freeze’s buyout not as a deterrent to firing him but as a more convenient mechanism. It’s the behavior of an institution that knows itself too well – like someone who builds the divorce settlement into their wedding vows.

In December 2021, Sonny Cumbie orchestrated what appeared to be a perfect audition. As Texas Tech’s interim coach, he dismantled Mike Leach’s Mississippi State team in the Liberty Bowl, displaying offensive creativity that makes athletic directors dream big dreams on small budgets. For Louisiana Tech, a program perpetually searching for innovation at discount prices, Cumbie represented a calculated risk: a quarterback whisperer who might turn Ruston into Conference USA’s laboratory for offensive evolution.

Twenty-four games later, that laboratory has produced mostly smoke. Cumbie’s record at Louisiana Tech reads like a scientific study in diminishing returns: 3-9, 3-9, and now 4-6, with an offense that’s regressed from five 40-point outbursts in 2022 to sporadic signs of life in 2024. The quarterback whisperer has largely gone silent.

But the real story isn’t in the wins and losses – it’s in the assembly of his coaching staff, where Louisiana Tech’s financial reality collides with its aspirations. “We are at the bottom rung of the assistant coach pay scale,” one fan noted, defending a collection of hires from places like Central Washington and Stephen F. Austin. Another countered, “None of these resumes are very impressive,” missing the point that impressive resumes rarely come at discount prices.

Consider the economics: Louisiana Tech offers Cumbie $900,000 annually, escalating to a modest $1 million, with $1.4 million to divide among ten assistants. In today’s college football, that’s like trying to build a sports car with spare parts from a bicycle shop. The program’s one notable coaching success story – Manny Diaz – stayed precisely one year before moving to bigger opportunities, a pattern that repeats itself across similar programs.

Cumbie’s tenure reveals the fundamental challenge facing programs like Louisiana Tech: they’re forced to bet on potential rather than proof, on coaches who might become something rather than those who already are. His staff, assembled from the outer reaches of college football’s map, represents either brilliant talent spotting or desperate bargain hunting, depending on your perspective and, crucially, the final score.

The tragedy isn’t that Cumbie is failing; his failure was priced into the system from the start. That Liberty Bowl victory, rather than launching a career, may have obscured an essential truth: miracles rarely come with multi-year warranties in college football’s modern economy.

At 10-24 overall, Cumbie has reached the point where even patient programs begin asking hard questions. But perhaps the most challenging question isn’t about Cumbie – it’s whether any coach, given Louisiana Tech’s resources, could build something sustainable from spare parts and promises.

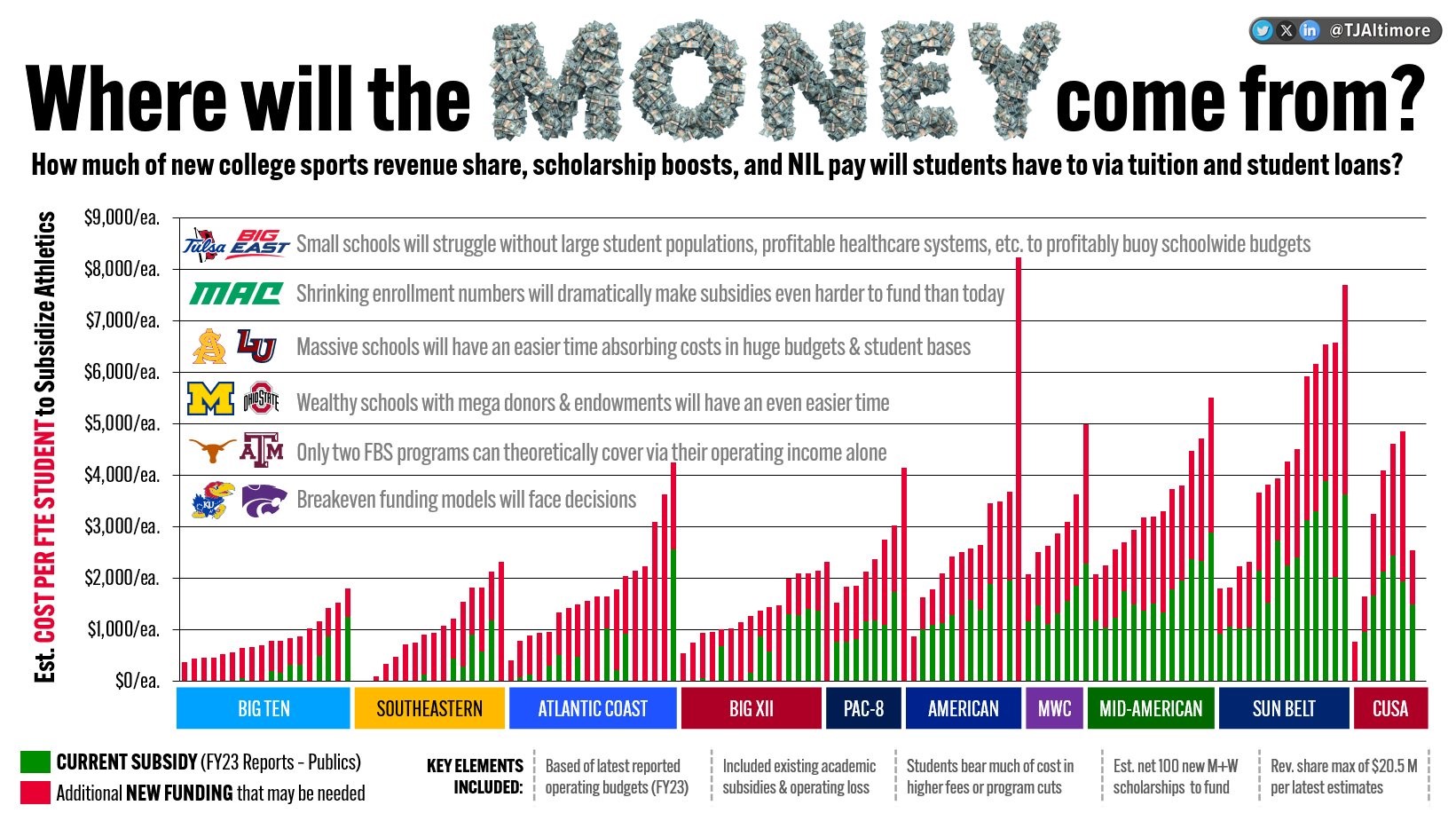

At Arkansas, they’re learning that timing in college football isn’t just about when to fire your coach – it’s about understanding when you’ve lost the luxury of waiting. The Razorbacks find themselves trapped in a maze of their construction: $40 million in new financial obligations from revenue sharing and settlements, a coach with a $10 million buyout that nobody can quite justify, and a contract clause that threatens to extend the very situation fans are desperate to escape.

Sam Pittman’s tenure reads like a cautionary tale about institutional decision-making. In 2021, when his team peaked at No. 8 in the country, Arkansas rewarded a coach who had never led another program with contract protections that assumed he had somewhere else to go. “Zero leverage in any negotiations,” as one fan put it, somehow translated into maximum security.

Now, at 5-5, with Louisiana Tech and Missouri remaining, Arkansas faces a peculiar mathematical crisis: two more wins, including a potential bowl victory, would trigger an automatic extension. It’s the kind of clause that transforms every touchdown into a threat, every victory into a potential long-term liability.

The administration’s whispered excuse – waiting for revenue sharing to settle before making any moves – ignores a crucial market reality: this may be the recent slowest season for Power Five vacancies. While Arkansas waits for perfect conditions, they’re watching their coach surrender 694 yards to Ole Miss in the most expensive audition for an extension in SEC history.

The genuinely revealing detail isn’t Pittman’s 28-30 record or even the historic defensive collapse against Ole Miss. The architecture of decisions led Arkansas to create a contract where success and failure became equally problematic. They built a system where winning just enough could be worse than losing outright.

As the Louisiana Tech game approaches, Arkansas faces a question beyond football strategy: How much does it cost to fix a mistake before it compounds itself? In a season where every other Power Five job remains secure, the opportunity to make a change has never been more evident – or more urgently needed before those two fateful wins can materialize.

The irony isn’t lost on a fanbase watching their program twist into financial knots. They know that while $10 million might seem steep to move on from Pittman, it’s a bargain compared to the long-term cost of letting him stay just long enough to earn the right to stay longer.

College football usually punishes hubris swiftly, but at UAB, they’re experimenting to see how long an administration can ignore reality. The results aren’t encouraging.

Trent Dilfer inherited Bill Clark’s masterwork – six straight winning seasons, two conference titles, a program that survived death once and emerged stronger. In less than two years, he’s transformed it into a case study in institutional denial. The on-field collapse would be enough: no first-half touchdowns in conference play, players ejected for shoving officials and post-touchdown headbutts. But it’s Dilfer’s “It’s not like this is freakin’ Alabama” dismissal that reveals the more profound dysfunction.

Athletic Director Mark Ingram’s steadfast support of Dilfer doesn’t read like loyalty so much as a refusal to acknowledge a $4.1 million mistake. The Jalen Kitna situation crystallizes the dynamic: faced with predictable backlash over signing a player dismissed from Florida on child pornography charges, the administration didn’t retreat – they dug in deeper, with Dilfer dismissing “initial headlines” as if they were discussing a parking ticket rather than felony charges.

The tragedy isn’t just in UAB’s regression from conference champion to cautionary tale. It’s in watching an administration convince itself that standing firm amid disaster demonstrates strength rather than stubbornness. While Dilfer jokes about his high school coaching days after 35-point losses, Ingram’s support transforms from professional courtesy to something more troubling: an administrator who can’t or won’t distinguish between standing by his coach and standing in the way of his program’s recovery.

The most revealing detail isn’t the empty stands or the lopsided scores – it’s the growing suspicion among boosters that this might be what program death looks like when it comes from within rather than from above. UAB once rallied a city to save its football team. Now they watch that same team dismantled by the people charged with protecting it, led by a coach who reminds them they’re not Alabama, backed by an AD who seems determined to prove it.

In the heart of Blacksburg, Virginia, a story of ambition, expectation, and the relentless pursuit of gridiron glory unfolds. Brent Pry, the man tasked with resurrecting Virginia Tech’s football program, stands at the center of this tale—a coach caught between the weight of history and the harsh realities of the present. Three years ago, Pry arrived at Lane Stadium with the promise of defensive brilliance and a return to the Hokies’ golden era. The faithful, hungry for success, embraced him. In early 2024, a staggering 75.1% of fans rated his performance at the top of the scale. Hope, it seemed, had found a new home in Virginia Tech. But in the unforgiving world of college football, where yesterday’s hero can quickly become today’s scapegoat, Pry’s journey has been anything but smooth. His first season in 2022 was a brutal 3-8 campaign—a record that would make even the most optimistic fan wince. It was as if the Hokies had forgotten how to win, their once-feared program reduced to a shadow of its former self. Yet, like any good underdog story, 2023 brought a glimmer of hope. A 7-6 record, capped by a Military Bowl victory, suggested that perhaps Pry’s process was beginning to bear fruit. The defense, long the backbone of Virginia Tech’s identity, cracked the top 20 nationally. For a moment, it seemed the tide was turning. But college football is a game of “what have you done for me lately,” and 2024 has been a study of unfulfilled potential. As November’s chill settles over the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Hokies sit at 5-4, their dreams of ACC contention fading like the autumn leaves. The faithful who once believed Pry would deliver an ACC championship now watch each game with bated breath, hoping for a miracle but fearing the worst. The numbers tell a story of their own. A 1-11 record in one-score games hangs around Pry’s neck like an albatross, each close loss a reminder of what could have been. It’s the statistic that keeps coaches up at night, poring over game film in search of answers that seem just out of reach. In the high-stakes chess match of college athletics, Pry’s moves are scrutinized with the intensity of a Wall Street earnings report. His contract, set to pay him $5 million a year by 2026, looms large—a bet placed by an administration hoping for a long-term payoff. But the clock is ticking in a world where patience is rare. As the 2024 season hurtles toward its conclusion, Brent Pry stands at a crossroads. The next chapter in this saga of redemption and reckoning will be in the coming months. In the stands of Lane Stadium, under the Friday night lights, the verdict on Pry’s tenure hangs in the balance—a reminder that in college football, as in life, the line between triumph and tribulation is often as thin as a goal line.